A little peek into the festivities at our Field of the Cloth of Gold Madrigal Dinner!

A little peek into the festivities at our Field of the Cloth of Gold Madrigal Dinner!

On April 22, 2018, Jouyssance and the Foundation of the Neo-Renaissance kicked off our 50th Anniversary celebration with a Madrigal Dinner. The Dinner featured music and narration based on The Field of the Cloth of Gold: a fabulous celebration during which the courts of Francis I and Henry VII put aside generations of conflict and joined together for diplomacy, feasting, music, sports, and more. In addition to the stories told during our Madrigal Dinner (including the tale of a pyrotechnic dragon released during the outdoor mass!), we created some posters with some of the more dramatic facts and figures we dug up while researching this event.

For nearly twenty years, Jouyssance Early Music Ensemble has explored and shared treasures of early music with our Southern California audiences, sponsored by our parent group, the Foundation of the Neo-Renaissance. Both organizations owe a great debt to Foundation president and steadfast Jouyssance bass, John Leicester. John, who also serves as SCEMS’ treasurer, recently retired from Jouyssance and from his position as FNR president. As we thank John and his devoted wife Dotty for their years of service, we look back on his legacy to us, and on the history of musicmaking that has led to today’s Jouyssance.

By Rick Dechance

Originally published in February 2009, Southern California Early Music News 33(6)

In 1961, the groundbreaking New York Pro Musica Antiqua performed at USC’s Bovard Auditorium. Outside, a young man named Michael Agnello passed out mimeographed flyers to recruit singers for a new early music ensemble here in Los Angeles. John had fallen in love with early music back in 1947 at a live performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo. He soon joined. This new group, called the Neo-Renaissance Singers, first performed at Loyola University in 1962. Not long after, accompanied by instrumentalists, they participated in the very first Annual Topanga Festival of Olde Musicke.

When the 1967 Festival was cancelled, the Singers decided to take matters into their own hands. Five members, including John, formally organized a new nonprofit, the Foundation of the Neo-Renaissance (FNR), charged not only with supporting the Neo-Renaissance Singers but with encouraging scholarship and performance of early music in general. Soon after, Robert Faris took over the position of director from Michael Agnello. Through the 1970s and 80s, the group continued to perform at fairs under their medieval gonfalon.

In 1990, Jim Stehn, a UCLA graduate student and principal trumpet and cornetto player with the LA Baroque Orchestra, grew frustrated with the lack of opportunities to perform Renaissance music. He organized a new group of amateur singers and instrumentalists, who voted to name themselves “Jouyssance” after the famous French Renaissance chanson, “Joyssance vous donneray.”

John Leicester joined Jouyssance two years later, and worked with Jim Stehn to bring Jouyssance under the FNR. Under the FNR’s sponsorship, Jouyssance became the successor to the Neo-Renaissance Singers. The group flourished under the direction of Chris Putnam and, later, Chris Kula. Jim Stehn took over as director, bringing professional singers and players into the group. During Jim’s tenure, the Jouyssance Soloists (including Belinda Wilkins, Nina Treadwell, George Sterne, Gregory Maldonado, and Bruce Birchmore) and the Jouyssance Choir presented several major concerts, including a performance of Josquin’s Missa L’homme armé super voces musicales. A recording of this Mass was released as Jouyssance’s first CD.

After Jim moved out of state in 1999, Jouyssance hired Dr. Nicole Baker, a professional singer and conductor, who had previously performed with them in concert. Under Nicole’s vivacious direction, Jouyssance continued to deepen both its musicality and its role as an “amateur” group—in the original sense of the word, as a place where the singers come together out of love for the music. Her past work in arts administration strengthened the ensemble as Jouyssance developed a regular seasonal schedule of performances, created annual promotional brochures, and released a new eponymous CD.

When Nicole had to step down in 2004 to care for her ailing mother, associate director Colleen Kennedy stepped out of the soprano section to serve as interim director for over a year. Colleen continues to support Jouyssance as the FNR’s treasurer, and helped arrange rehearsal space for Jouyssance at her church. During this time, Jouyssance’s instrumentalists, coordinated by longtime Jouyssance countertenor and woodwind player John Robinson, officially organized under the FNR as Jouyssance des Instruments.

A yearlong search for Nicole’s successor brought us Dr. Carol Lisek. Carol combines thoughtful programming with a love of theatricality, which lent itself especially to our early baroque repertoire. Nowhere was this more evident than our first joint concert with the Los Angeles Recorder Orchestra, a dramatic performance of Purcell’s masque from Timon of Athens. After Carol stepped down to pursue her academic career, Nicole Baker returned, and is currently in her eighth season with Jouyssance.

“Jouyssance” has many meanings – some of them, especially during the Renaissance period, racy – but first and foremost, it means a deeply fulfilling joy. Over a hundred singers and instrumentalists have shared our stage, and all have been touched by the camaraderie, musicianship, and sheer joy of creating music that the Neo-Renaissance Singers and Jouyssance have provided. Throughout our history, with its many changes, there has always been John Leicester. His contributions are innumerable. From maintaining the library to keeping attendance, whether through the annual FNR/SCEMS party or an FNR calendar, both as a singer and as founder and longtime president of the FNR, John has worked to create and sustain this wonderful organization that brings people together to create art and artistry. We will miss singing with him greatly, but we will never forget his gifts to Los Angeles’ musical culture, and to all of us who have had the deep and fulfilling joy of performing in Jouyssance.

by Alexandra Grabarchuk, Ph.D.

This essay originally appeared in the newsletter of the Southern California Early Music Society (SCEMS). Reprinted with permission. Visit the SCEMS website to join the Society and receive regular Southern California early music news and essays.

“…there are no objective real works, any more than there are objective real authors. It depends on our interest, that we build a certain image of a certain author, a philosopher or a composer. Every time has its own image of Plato and Kant, every time has its own image of Bach and Mozart. The more we fix their images, the more we are interested in their authenticity. It is only from these fixations that it could be important to raise the question whether a certain work was in reality written by Kant, or Mozart, or by some unknown author: the intrinsic philosophical or musical significance remains always the same. Or do you really believe that the meaning of the Critique of Pure Reason would diminish as soon as somebody had discovered that it was not written by Kant? All these considerations concerning authenticity are part of our attitude in the twentieth century.” ~ Wim van Dooren, “General Problems of Authenticity in the Context of Renaissance Philosophy” in Proceedings of the International Josquin Symposium, Utrecht 1986.

There is no other pivotal figure in music history about whom we know so little. Josquin is loudly touted as the central figure in Franco-Flemish music, yet there are less than two dozen items of archival data that provide any biographical information about him. Because of this scarcity, the temptation has been to scavenge information about anyone with a similar or closely related name. As David Fallows points out in his monumental Josquin, there are at least three other figures (Juschinus de Kessalia, Johannes Stokem, and Josquin Steelant) whose documents have erroneously been a part of the Josquin story, muddling up birth dates and questions of location and stylistic chronology until the late 1990s.

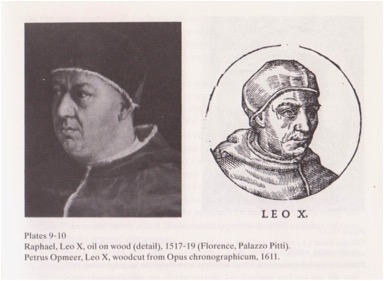

Scarcity of facts notwithstanding, Josquin continues to tantalize scholars, often to the point of great personal attachment. Willem Elders explains this attachment to the historical figure of Josquin through the prevalent and widely-circulated image of the Opmeer woodcut:

Josquin woodcut by Opmeer

And yet even this explicit portrayal of the composer comes to us from such a distance that its resemblance to the person Josquin des Prez is questionable. Firstly, the woodcut was copied from a painting, so it’s already a second-level representation. Yet even the verisimilitude of the painting is questionable at best, as Opmeer himself explains that it was painted after Josquin’s death and put in the Church of St. Gudule in Brussels as a way of immortalizing his memory. Not only was it painted posthumously, but 16th century painters did not share the realist values which emerged in post-Revolutionary France a few centuries later. Instead, the 16th century was marked by mannerism, a style of painting characterized by elongated figures, complex poses, and distorted settings – in other words, the unrealistic was in vogue. Judging by the woodcut, Josquin’s portrait was sufficiently simple that it’s hard to imagine it was much distorted. Regardless, one must keep in mind that it was painted by someone who didn’t necessarily value realism.

In addition to all this, the skill of the woodcutter must be taken into account. By comparing existing paintings with their Opmeer woodcut counterparts, Elders convincingly argues that, even when copying a painting of a living person whose countenance was more familiar and widespread than that of Josquin, the resemblance is sometimes questionable. In this side-by-side comparison of a painting and Opmeer woodcut of Pope Leo X, it is evident that although the general impression of the face is somewhat similar in both instances, it is not an overwhelming likeness.

Painting and Opmeer woodcut of Pope Leo X

Although Raphael did not paint in the Mannerist style, it is unclear how much the portrait of Pope Leo X actually resembled its model. What is clear, however, is that there are striking differences between the painting and woodcut.

In other words, the image of Josquin scholars have clung to as the definitive visual representation of the composer may not be definitive at all. It is merely a fixed image the veracity of which we are unable to ascertain, and as Wim van Dooren points out in the epigraph, “the more we fix [historical figures’] images, the more we are interested in their authenticity.” Our idea of Josquin is a construction, as all historical work must be to some degree, and it has undoubtedly been shaped in part by this image, which does not necessarily stand out for its artistic excellence or exacting verisimilitude, but merely because it is the one image of Josquin that has survived.

The word canon signifies a body of work bound by some principle – whether it’s the canon of Romantic masterworks, the canon of classical music in general, or the canon of a particular composer. The idea of the canon is often a fairly useful tool that allows music historians to talk about disparate pieces as belonging to a unified body of works. It is, however, an inherently problematic concept, and the problem becomes evident when one begins examining the unifying principle more closely. What counts as a Romantic masterwork? Is there a particular date past which musical works no longer count as Romantic? Is there a specific zeitgeist that imbues a piece with the Romantic spirit? How is this determined? If we speak of “classical music” as a whole, what is included in that canon? Although it seems that the canon of a particular composer would be the most easily determined – after all, he or she either wrote the piece in question or not – it is still a problematic situation. The scarcity of historical evidence in Josquin studies brings these problems of authorship to light in a unique way.

There are two types of conflicting attributions: those that offer no fundamental difficulty of resolution, and those that do. The first type of conflict is the kind that can be easily resolved through reliable historical evidence. The far more interesting type of conflict is one where no one lays an obvious claim to the particular composition; it is in these situations where scholars must develop other criteria for authenticity in order to solve the mystery. This frequently involves some investigative work of sources Finally, scholars can turn to some type of stylistic analysis, comparing the piece to other pieces securely authenticated as belonging within the canon and keeping an eye out for features unique to, or typical of, other works by the composer.

What we have is a loosely formulated general consensus about which pieces were actually written by Josquin. I believe this idea of a group of works with a highly permeable boundary across which pieces move easily depending on current states of historical knowledge applies to any canon constructed around one composer. Below, I explore a group of works that have been attributed to both Josquin and Pierre de la Rue, highlighting the difficulty of pinpointing authorship and “authenticating” any given piece of music as belonging to one canon or another.

Pierre de la Rue was arguably the finest composer of the Habsburg-Burgundian court at the turn of the 16th century. Yet after the 1530s, his fame waned and his music began to be copied without reference to his name. Previously attentive ears began to tune out of the stylistic differences between his work and that of Josquin, and a number of publishers and music scribes confused the two when making copies of the following eight works.

I wish to examine and comment on the techniques by which J. Evan Kreider analyzes and attributes three of these works: one to Josquin, one to La Rue, and one to an anonymous third party. Through this examination, I hope to bring to light the methodology through which a “canon” is established, and demonstrate that canons as we know them are always fluid, permeable, and constructed.

The Missa de beata virgine, composed just after the turn of the 16th century, is a paraphrase mass that, judging by the number of surviving sources, appears to have been extremely popular. It is noted for its unusual voicing – the first two movements are written in four parts, and the last three in five. Josquin was not known to have done this elsewhere, yet Kreider firmly places this piece within the Josquin canon, arguing that the misattributions of all three masses listed in the table above are resolved with relative ease. It seems that erroneous attributions of all three are found either in sources that contain conflicting attributions themselves, or have been found unreliable for other reasons. Let us examine how Kreider comes to this conclusion.

This mass does not seem to be a questionable case, as the numbers are clearly in Josquin’s favor. Of the surviving vocal sources, twenty-eight name Josquin as its author, three present the work without attributing it to a composer, and only one source points to La Rue. Of the surviving instrumental arrangements, ten indicate Josquin as composer, and the other two refrain from attributing it altogether. Yet it’s difficult to attribute it to Josquin with absolute certainty simply based on numbers – after all, scribes and copyists could have mistakenly perpetuated an erroneous attribution. The deciding factor comes from three places: Glarean’s mention of the mass, the Habsburg-Burgundian scriptorium, and the unreliability of the source that attributes it to La Rue.

The only theorist to quote from this mass, Glarean mentions it in his Dodecachordon – and not only does he unhesitatingly name Josquin as the composer, he brings it up specifically to illustrate Josquin’s style of writing and masterful use of the modes. In other words, at the time it was felt that Josquin’s authorship of this piece was not only common knowledge, but exemplary of his style. This in itself does not constitute proof, although it is fairly convincing. But when one examines the manuscript sources published by the Habsburg-Burgundian scriptorium (the workshop responsible for putting out the best copies of La Rue’s masses), which is generally found to be an accurate source for attributions to La Rue, all three name Josquin as the composer of this mass. Finally, an extremely unreliable source which inexplicably splits up the movements of the Mass and attributes some to La Rue, and some to Josquin. From these disparate facts, it appears safe to say that the Missa de beata virgine was composed by Josquin.

Unlike the preceding case, there are very few surviving sources for this chanson, making it more difficult to lean one way or the other merely by looking at numbers. Cent mille regretz has been preserved in only three sources, one of which points to Josquin, one to La Rue, and one which declines to attribute it at all. Here, Kreider turns to stylistic analysis to help resolve the mystery. He points to three stylistic gestures as being indicative of the writing of Pierre de La Rue: strict canonic writing in the two lower voices (of the two composers, La Rue seemed to be particularly fond of canons, particularly in the tenor and/or bassus), the composer’s reliance upon a motive (the interval of a fourth generates much of the material in this chanson), and the dense texture of the chanson. Kreider’s conclusion: “[a]lthough Renaissance musical fingerprints are uncommonly difficult to identify, we can safely conclude that Cent mille regretz is the work of La Rue.”

The history of this piece is indicative of the bewildering array of attributions which occurred when 16th century musicians came upon a piece whose authorship was unclear. In this situation, the information that has trickled down to us in the 21st century first passed through the ears and minds of many a 16th century musician, with many different ideas about what the piece sounded like and where it fit into the grand scheme of things. For example, an ornamented keyboard transcription of the piece was attributed to Hans Buchner by his student, the Swiss copyist Fridolin Sicher. Later, an anonymous hand corrected this attribution to Josquin, but then scratched it out and connected it back to the original Buchner attribution.

Yet looking at the musical characteristics, Kreider argues that this was the work of neither composer. He presents the following points: 1) La Rue was not known to use the bar form elsewhere, 2) the voicing does not correspond to the previous work of either composer, 3) the borrowed melody occurs in the bassus, 4) the upper parts appear to be unrelated to this borrowed melody, and do not share motives with one another, and 5) the melodic writing “reflects the style of the previous generation.” The agenda one senses behind Kreider’s argument is that the piece was not sufficiently well-written to be attributed to either composer. It is difficult to say with certainty how persuasive the argument is, but it is clear that since musicians of the time didn’t know what to do with the piece, it didn’t strictly fit the compositional style or criteria of any one composer.

Through this presentation of canon-forming methodology, I hope to have demonstrated the tentative quality of this type of work. As inwardly compelling as stylistic analysis may be, or as persuasive as the numbers might be in any given case, Joshua Rifkin’s suggestion that a Josquin canon does not and cannot exist rings true. It seems that the best we can do with the scant historical information we have is to arrive at some temporary consensus regarding a particular piece, until new information is brought to light.

By Nicole Baker, PhD

This essay originally appeared in the newsletter of the Southern California Early Music Society (SCEMS). Reprinted with permission. Visit the SCEMS website to join the Society and receive regular Southern California early music news and essays.

The music of the Iberian Renaissance reflects the many forces that shaped its culture: its Moorish and Jewish populations, the Catholic Church, the wandering minstrels and troubadours that criss-crossed Medieval Europe, its links to England, influences from its colonies around the world, and local popular music traditions. Renaissance music from Spain has long been favored by audiences and performing groups alike for its passion and beauty. Names like Victoria, Morales, and Guerrero populate concert programs of choirs of all levels. Medieval music specialists like Jordi Savall have allowed us to experience the exotic, Moorish-flavored beauty of such Spanish collections as the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat, the Cantigas de Santa Maria, and the Codex Calixtinus.

Thanks to a paucity of sources, audiences have had fewer opportunities to hear music from Portugal. But a chance encounter with a Naxos CD titled simply “Portuguese Polyphony” has opened this listener’s ears to this wondrous repertoire. Jouyssance has already presented a heavily Portuguese Iberian Twelfth Night, and will reprise some of the same music (and add a lot more!) at its April 21 concert at the Muckenthaler Cultural Center in Fullerton. Music of Portugal will also form the backbone of Jouyssance’s next CD, Cantiga: An Early Music Journey through Iberia.

The lack of sources for this music starts at the beginning of Western music history: most Medieval sources of chant are lost, with the earliest preserved at the Cistercian abbey of Alcobaça, and at the convents of Lorvão and Arouca. The first cathedral music schools – strong indicators of a growing musical tradition – were founded in the 11th century, with Lisbon’s founded a century later in 1150.

Secular minstrel music, sung in a Galician-Portuguese dialect, flourished from the late 12th century well into the early 14th, with the reign of Afonso III (1248-79) being a particular highpoint. Influenced by the Provençal troubadour tradition, most of the songs were either epic heroic ballads or courtly love songs. King Dinis (1261-1325) was himself a troubadour and musicologist recently discovered some fragments of his music.

Astonishingly, no polyphonic music survives from the 14th and 15th centuries, despite evidence that much existed. The earliest surviving works do bear markers of political and cultural links to England, and influence from the music of Henry VI's chapel can be heard.

The first major composer was Pedro do Porto (known in Spain as Pedro de Escobar) who served the court of Queen Isabella of Spain. He served as maestro de capilla at Seville Cathedral from 1507 to 1514 and later mestra de capela to Cardinal Archbishop Afonso of Évora in eastern Portugal. Évora Cathedral would prove to be a major musical center: some of its most important musicians included Manuel Mendes (c.1547-1605) , Filipe de Magalhães (c1571–1652) and Diogo Dias Melgás (1638–1700).

Manuel Cardoso

Perhaps more critical was its cathedral school, which produced musicians who worked throughout Iberia and beyond: Manuel Cardoso (1566–1650) and Duarte Lobo (c1564/9–1646) worked in Lisbon and elsewhere; and the Spaniard Estêvão Lopes Morago (c.1575–after 1630) served Viseu Cathedral.

Renowned in his time for his music, the devout Carmelite friar Cardoso enjoyed the patronage of King João IV, who kept a portrait of the composer in his music library. Cardoso had strong ties to the royal families of both Spain and Portugal, with King Philip IV a key later patron.

Cardoso’s beautiful Magnificat secundi toni will appear on the upcoming CD as well as the Muckenthaler program. Although he lived well into the Baroque era, Cardoso’s style remained rooted in the stile antico of the late Renaissance polyphonists. Composed by 1605, and published in Lisbon in 1613, the Magnificat follows the traditional harmonic and rhythmic style of Palestrina, although there’s a surprising amount of chromatic spice and dissonance. His use of augmented chords show an awareness of the new "crunchy" harmonies of the early Baroque, and creates a particularly expressive language helped by occasional passages of homophony that highlight the text.

Another important cathedral chapel was that of Braga, whose first known mestre de capela was Miguel da Fonseca (fl.1530–1544). His son Manuel was also a skilled composer, and his lovely Natus est nobis appears on Jouyssance’s first CD.

The Augustinian monastery of Santa Cruz at Coimbra served as a major musical center in the 16th and 17th centuries, employing the versatile Pedro de Cristo (c1550–1618). Although known best in his time for his secular works and sacred villancicos, his motets show his skill at polypohony. He was also known as a performer at the keyboard, the harp, the flute, and the dulcian, an ancestor to the bassoon.

Jouyssance has performed works that show two distinct styles: his sacred works are expressive and even dark in color. His bouncy villancicos are full of syncopation, and recall modern Mariachi music!

Joao IV

João IV (1604–1656), also known as King John IV, was to some extent the Henry VIII of Portugal. Trained as a musician from childhood, he amassed the largest music collection of his time, which, based on a partial catalogue that survives, included the only copies of numerous Spanish and Portuguese composers. The collection was sadly destroyed in the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. A skilled composer himself, and a possible student of Cardoso, only a handful of his works survive.

The political union of Portugal and Spain between 1580 and 1640 created new career opportunities for Portuguese composers both in Spain and in the Spanish New World. Prominent among them were Estêvão de Brito (c.1575–1641), maestro de capilla of Badajoz and Málaga cathedrals, and Jouyssance favorite Gaspar Fernandes (c.1570–1629), who crossed the Atlantic to become maestro de capilla of Puebla Cathedral in Mexico. He often incorporated rhythms from native cultures into his own works, which includes 250 songs and villancicos in Spanish, Portugese, Nahuatl, and various African dialects.

Portuguese polyphony continued to flourish throughout the 17th century. But the dawning of the Baroque brought about a major shift in patronage from the Church to courts throughout Europe, but particularly in Italy and France. Opera and new instrumental forms gained supremacy, and the glory of Iberian sacred music faded into obscurity.

In keeping with its mission of presenting gems as yet unknown, Jouyssance will present a concert of this beautiful music Thursday, April 21, at 7:30 p.m., at the Muckenthaler Cultural Center, 1201 W. Malvern Ave., in Fullerton.